|

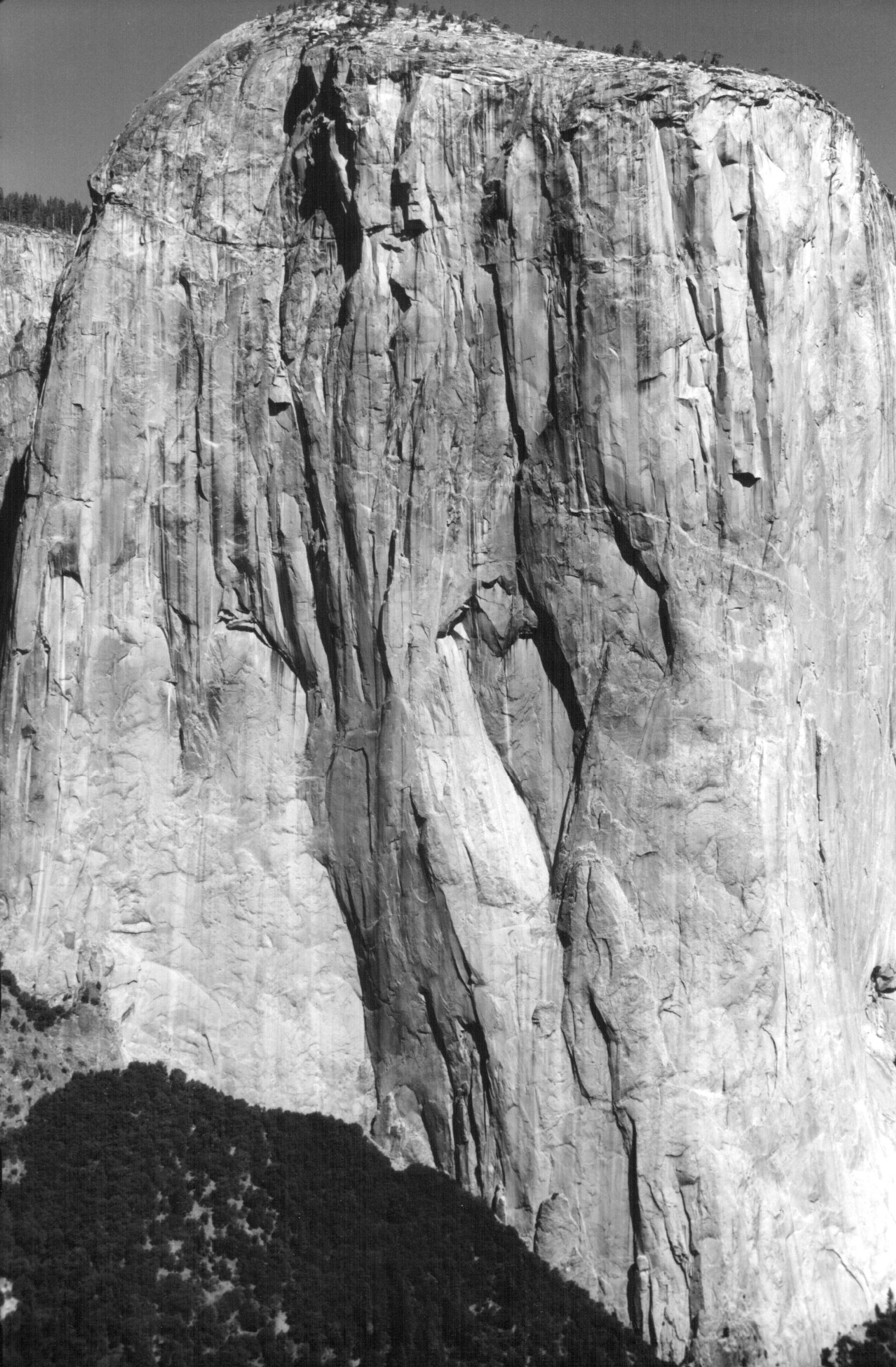

The southwest face of El Capitan is home to two world class routes named

in honor of the founding fathers of Yosemite climbing:

John Muir and John Salathé.

The southwest face is also El Cap’s finest wall.

John Muir traveled all the way from Scotland to become

Yosemite’s first climber and to teach us how to do it on tangible and

intangible levels. “Whenever

I met a new plant I would sit down beside it for a minute, or a day, to

make its acquaintance, and to see what it had to tell” (John Muir,

played by Lee Stetson in the Yosemite Theater). And

again, “I only went out for a walk and finally concluded to stay out

till sundown, for going out, I found, was really going in.”

John Salathé came from Switzerland. His

Lost Arrow Chimney and Sentinel Rock climbs set new climbing standards.

Salathé’s

climbs were lightweight, huge commitments into unknown territory that

lasted up to five days. Robbins,

the leader of Yosemite’s next generation acknowledged:

“He

had this sense of style, of never taking the easy way out.

Of all the climbers we knew, he was the one who would push the

furthest, without resorting to bolts, so he became our, kind of,

standard to aim at.” (Royal

Robbins, interview by Kristi Denton Cohen, “Vertical Frontier”)

Salathé

so inspired us that in 1960 Chouinard and the Camp 4 community named El

Cap’s southwest face the Salathé Wall.

A significant moment occurred here in 1988 when Paul Piana and

Todd Skinner topped out on the Salathé Wall after having completed the first ever free ascent of a big

wall. It was a world class

achievement. As Piana

belayed the final pitch his primary anchor, a large block, suddenly slid

from its perch and pushed them off the wall.

They were left injured, hanging by the thread of a nearly

completely shredded rope. Their

survival was a miracle. Nothing

happens by accident, so what’s happening here?

I liken Piana and Skinner’s situation to that of the Martin

Handcart Company, Mormon pioneers who trekked across the Great Plains in

survival conditions. An old

man from this company, his face white with emotion, spoke of their

experience calmly, deliberately, but with earnestness and sincerity:

I

have pulled my handcart when I was so weak and weary from illness and

lack of food that I could hardly put one foot ahead of the other.

I have looked ahead and seen a patch of sand or a hill slope and

I have said, I can go only that far and there I must give up, for I

cannot pull the load through it.

I

have gone on to that sand and when I reached it, the cart began pushing

me. I have looked back many

times to see who was pushing my cart, but my eyes saw no one.

I knew then that the angels of God were there.

Was

I sorry that I chose to come by handcart?

No. Neither then nor

any minute of my life since. The

price we paid to become acquainted with God was a privilege to pay, and

I am thankful that I was privileged to come in the Martin Handcart

Company. (ENSIGN,

February 2006)

The message, I believe, is this:

it is apparently worth the price of miracles for us to be

reminded that, no matter how grand our achievement, we did not do it

alone.

THE SALATHÉ WALL, from the summit

of Lower Cathedral Rock, Yosemite National Park, California, 30

September 1961.

|