|

||

|

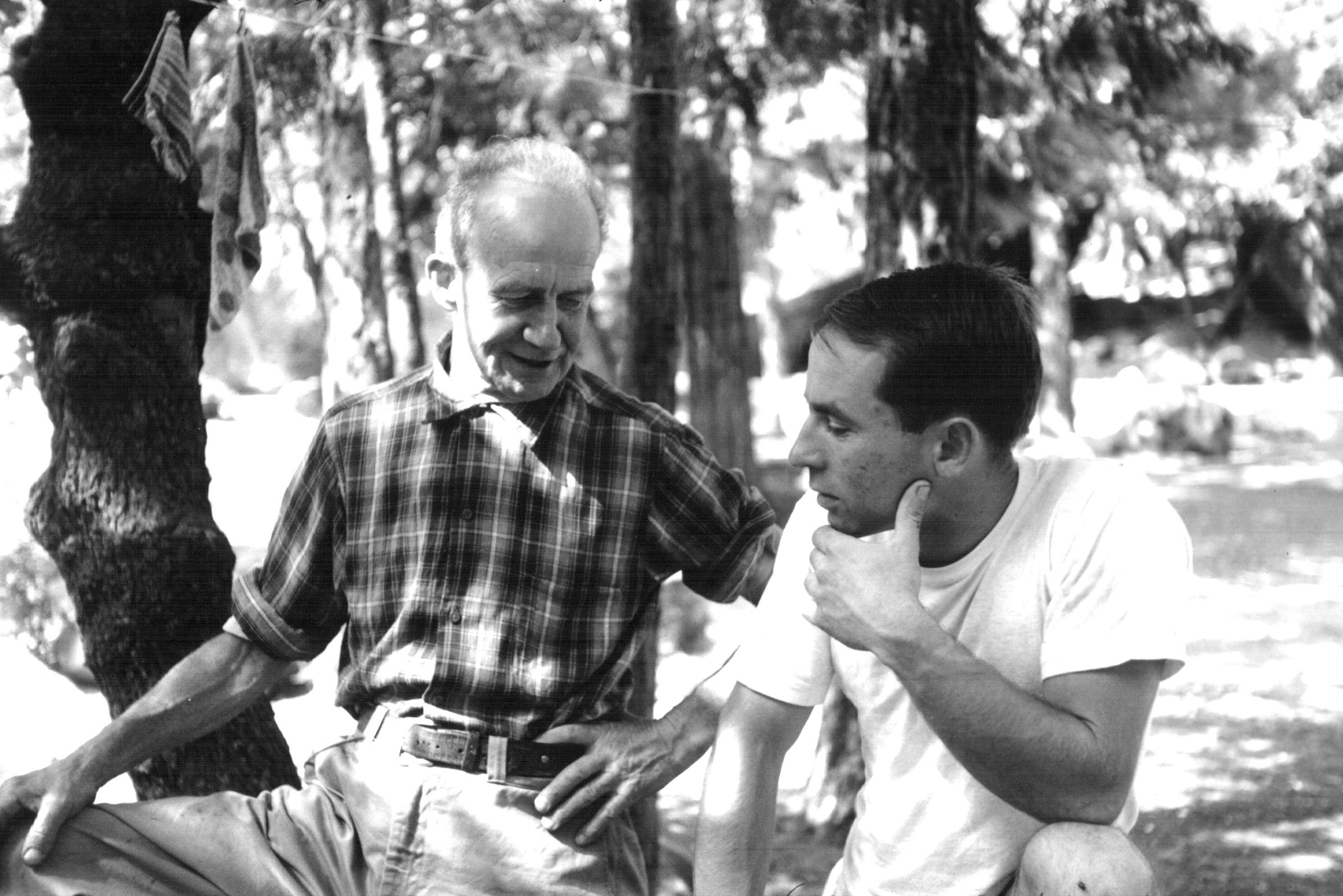

SALATHÉ AND CHOUINARD, 1964 |

||

|

In the fall of 1964 two great pioneers of American climbing met at Camp

4. Both were master

blacksmiths. Both

visionaries, able to see the way. Both

leaders in their generations – John Salathé and Yvon Chouinard.

Royal wrote about how deeply Salathé’s example

influenced us. He said, in

addition to Salathé’s great technical skill and the forging of special carbon vanadium

steel pitons, it was his “sense

of style that would set a standard for generations of climbers to come.

In those days, Yosemite climbing required the occasional bolt, or

sometimes a string of them, to overcome truly blank sections of

otherwise climbable rock. There

always existed the temptation to get out the drill before it was

absolutely necessary, to take the

easy way out, rather than screw up one’s courage, and work

tirelessly and inventively to find a way to get up without resorting to

the detested expansion bolt.

“Amazingly, Salathé

never succumbed to this temptation.

His bolts were always deemed by later parties, ‘justified.’

How hard that is to do. How

remarkable that he did it in his day, absent the goad of competition.

No one would have faulted him for placing twice as many bolts.

He was competing only with himself.

What was he thinking? Where

did he get this sense of style? Why

did he set these almost impossibly high standards for himself?

We don’t know. He

didn’t write or talk about these things.

His eloquence on such matters was pure action, and his actions

were to us spellbindingly persuasive.

American climbing would have been quite different had those of us

who followed in Salathé’s footholds not been so deeply impressed by the courage and

commitment to excellence of this thoughtful, taciturn, Swiss blacksmith

who came to California and taught Americans a thing or two about

climbing, and on whose shoulders so many of us have stood, reaching for

higher holds.” (Royal

Robbins, Voices from the Summit)

Writing about John Salathé, and the Lost Arrow chimney climb they did

together, Anton Nelson said: “One

thing is not an adequate

motive for climbing; that is egotism or pride.

Yes, most of us who climb usually play to the crowd, as such an

article as this may demonstrate. However,

mere self-assertion alone has a low breaking point.

To keep going day after day under heart-sickening strenuousness

requires a bigger, more powerful faith than in oneself or in any concept

of superiority.” (Sierra

Club Bulletin, 1948)

Salathé possessed a sensitivity and strength beyond what the rest of us

normally apply to life. For

example, he listened to the council of angels and benefitted thereby.

In short, he owned the most valuable attribute a traditional

climber can possess – “he knew things he didn’t know.”

Salathé

showed us what was possible. He

was a kind of “father” of Yosemite rock climbing.

One decade later Yvon

Chouinard also saw the need for tough, well-designed pitons; and an

inspiring standard in American wall climbing.

Chouinard’s Lost Arrow pitons were patterned after John Salathé’s

and his Muir Wall set a new standard on El Capitan. |

||