|

“Nothing contributes more to Yosemite’s preeminent grandeur than a

3,000-foot white monolith standing at the gate to the Valley:

El Capitan

. ‘The Captain’ it

indeed is, for it commands the attention and respect of everyone

entering

Yosemite

. Its light igneous rock is

called

El Capitan

granite. From the south to

the west buttress, four great routes lie on this fine, hospitable

granite. But the southeast

face is different, for the granite is displaced in the center of that

wall by brittle black diorite. This

diorite forms a crude map of the North American continent, whence the

name, ‘North America Wall.’

“Because of its grim aspect, this dark wall was left untouched

while the more obvious and esthetic lines on the southwest face were

climbed. But the inevitable

attraction of a great un-climbed wall finally prevailed, and in October

of 1963, Glen Denny and I made several probes, reaching a

high point

of 600 feet. The

aid-climbing was unusually difficult.

Promising cracks proved barely usable.

On the third pitch nearly every piton was tied off short.”

(Royal Robbins, AAJ, 1965)

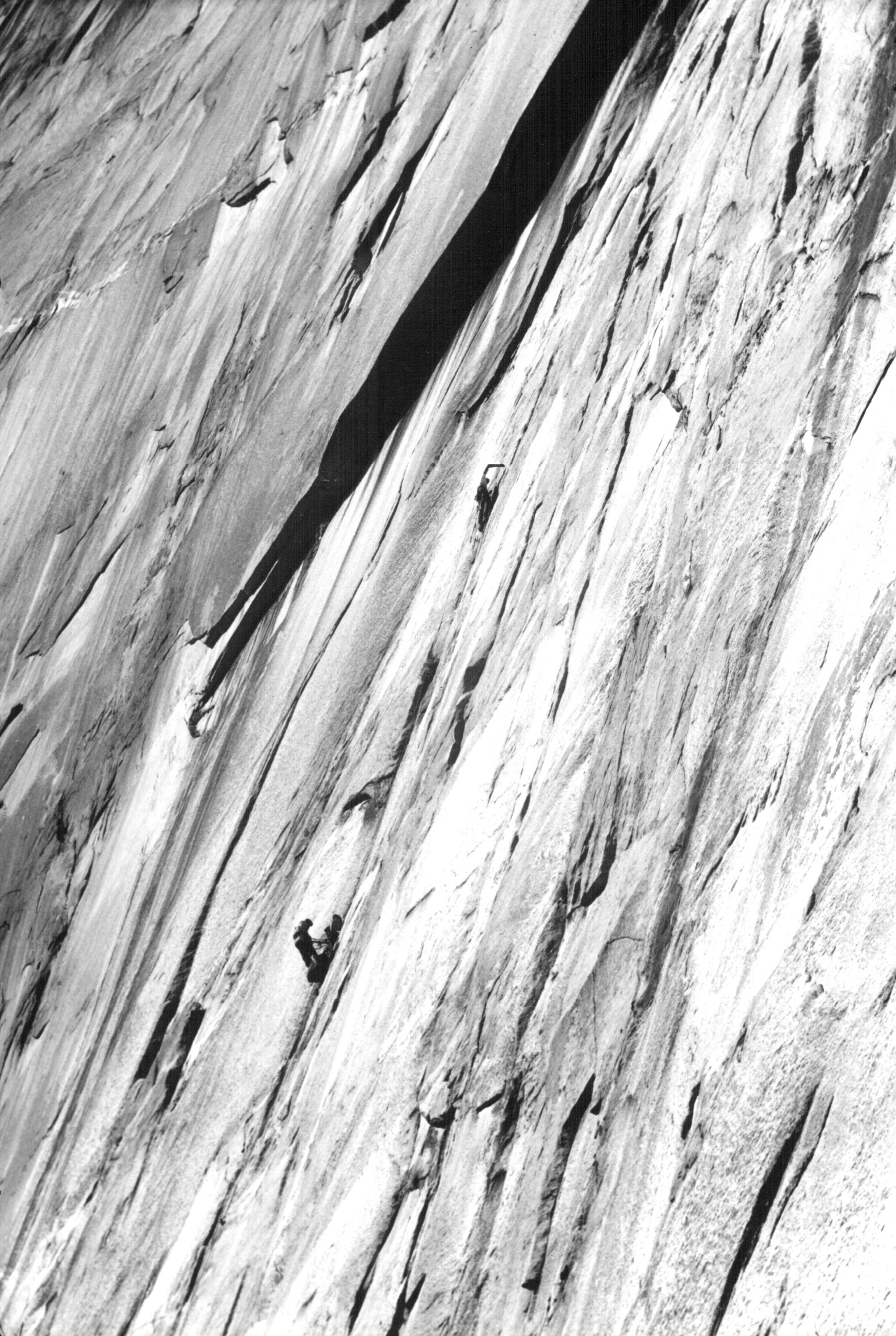

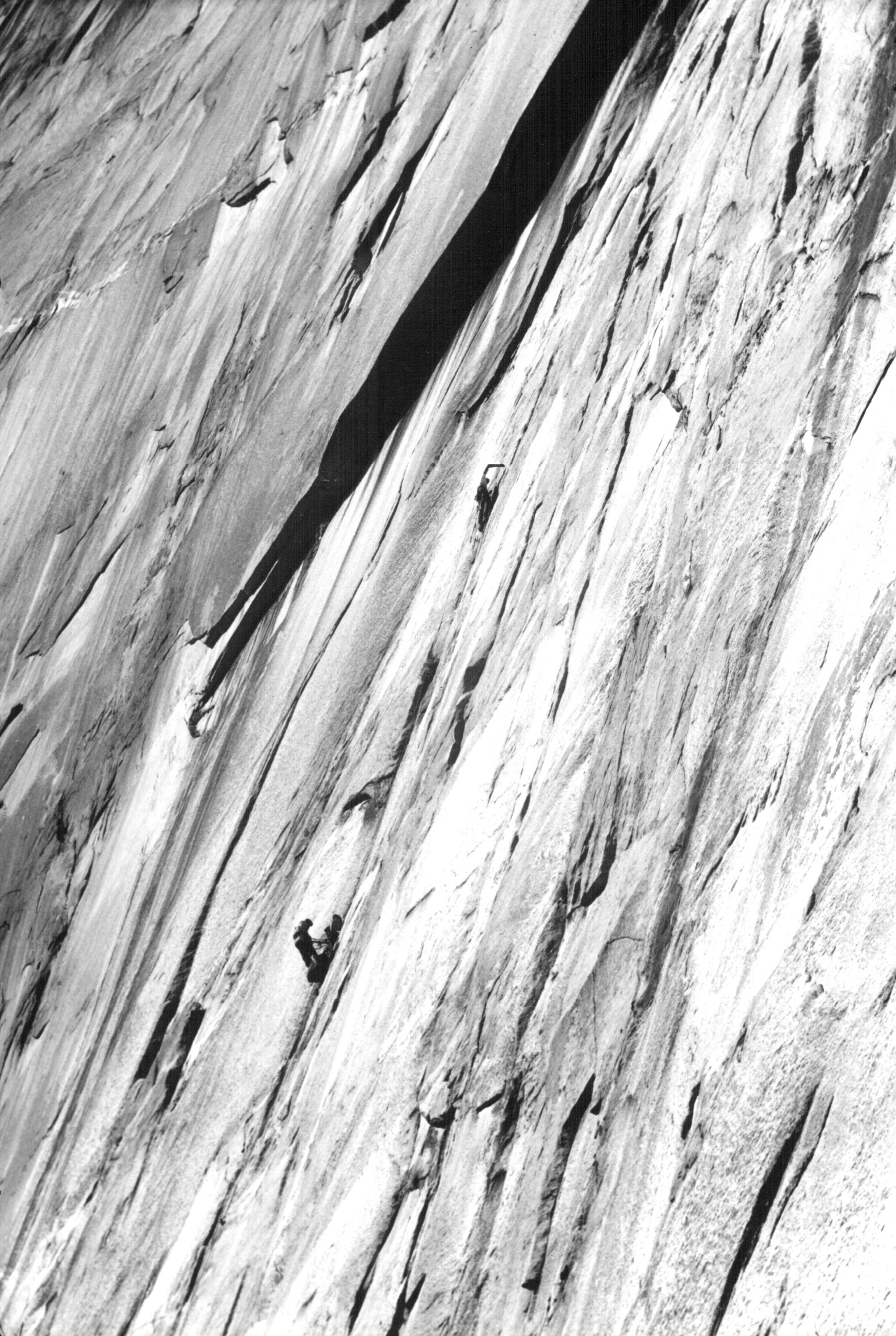

In this photograph Denny leads the fourth pitch, belayed by

Robbins. Exploration of the

North America Wall had begun. We

returned in the fall of 1964 for an all-out effort.

“We half-expected (and half-hoped) others would do the climb

before we returned. But when

Tom and I arrived back in

Yosemite

the wall stood somber and still virgin – waiting.

We all felt similarly about the climb – it was not an appealing

wall. It did not have the

elegance or majesty of the southwest face.

The treacherous dark rock, the difficulty of retreat due to great

overhangs and long traverses, the absence of a natural route, and

finally the apparent necessity for many bolts rendered us not happily

enthusiastic about the venture. A

large part of our individual selves did not want to attempt this face.

But another part was lured on by the challenge of the greatest

unclimbed rock wall in

North America

.” (RR, AAJ)

Roper commented on the North America Wall climb:

“If you assemble the four best rockclimbers in the country –

probably the world – and stick them onto a steep, unclimbed

Yosemite

cliff, you may not have too many stories to tell afterward.

On October 31, nine and a half days after starting, the quartet

had completed the most difficult rock climb ever done.

The exposure had been awesome - much more so than on the Nose or

the Salathé –

and the nailing difficulties unprecedented.

Mightily determined to avoid bolts (only thirty-eight were

placed), the team performed aid miracles and made wild pendulums and

traverses. The diorite,

fractured and lacking structural integrity, belied the fact that

Yosemite

usually had the best rock on the planet; loose flakes and strange cracks

presented special problems. It

had been hot at first; stormy later.

Still, all such things were expected, and the team simply dealt

with them one step at a time.” (Steve

Roper, Camp 4)

ON

THE NA WALL, the first reconnaissance by Royal Robbins, and Glen Denny

to 600 feet, October

1963. The ascent of the full

route took place one year later during 10 days of October 1964, by Robbins, Pratt, Chouinard, and Frost.

The North America Wall, El Capitan,

Yosemite Valley,

California.

|