|

Roper

writes about the natural features of the Salathé Wall

climb:

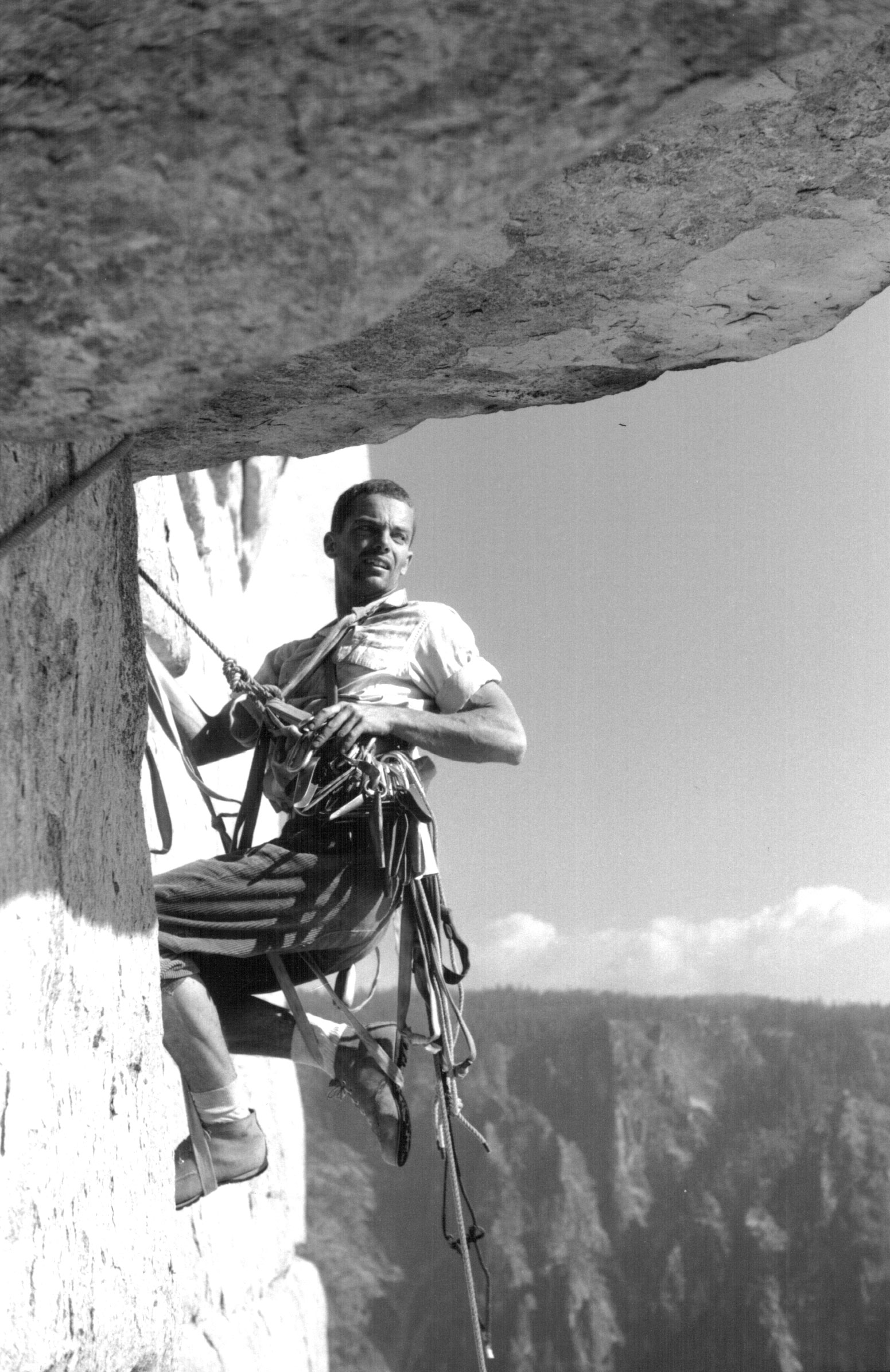

“Most impressive of all were two awesome, and

connected, sections near the top: a

tiered ceiling they simply called the Roof and the overhanging wall just

above, dubbed the Headwall. These

two sections didn’t need complex names; they are classics of the

genre. The ceiling jutted

out perhaps twelve feet, yet the tiers contained hidden but near-perfect

cracks, and Frost nailed this quickly.

Above lay a 150-foot headwall, tilted five degrees beyond the

vertical. Bottomed and

flared cracks shot up this sober and grainy expanse, but pitons

nevertheless stuck long enough for upward progress.

The exposure defied description.

An object let loose from here will spin free for about 400 feet

before brushing the near-vertical cliff below.

Seconds later it will kiss the wall two or three times before

exploding into the forest, 2,000 feet below.”

(Steve Roper, Camp 4)

We had spotted the Salathé

Roof, and the single crack running up the Headwall, during our

reconnaissance from El Cap Meadow several days before beginning the

climb. It looked

spectacular, even from the ground. But

the full force of the exposure Roper describes did not reveal itself

until we started out into that spacey place.

It was an experience of a lifetime.

HEADWALL ROOF, Tom leads

pitch 29, the Salathé Wall, El Capitan,

Yosemite National Park, California.

First ascent by Royal

Robbins, Chuck Pratt, and Tom Frost, 9˝ days, September 1961.

|